"Data Strikes": A New Form of Leverage for Tech Users?

This is a guest blog post written by Nick Vincent, a PhD Student from the People, Space, and Algorithms Research Group at Northwestern University.

When it Comes to Your Relationship with Tech Companies, You Have More Power Than You Think

Many people are increasingly concerned about the behavior of tech companies, but feel powerless to change these companies’ behavior. For these people, we have some good news: In a recent research paper (a collaboration with Dr. Brent Hecht and Dr. Shilad Sen), we presented early evidence that the public may be able to exert more leverage against tech companies than is commonly understood.

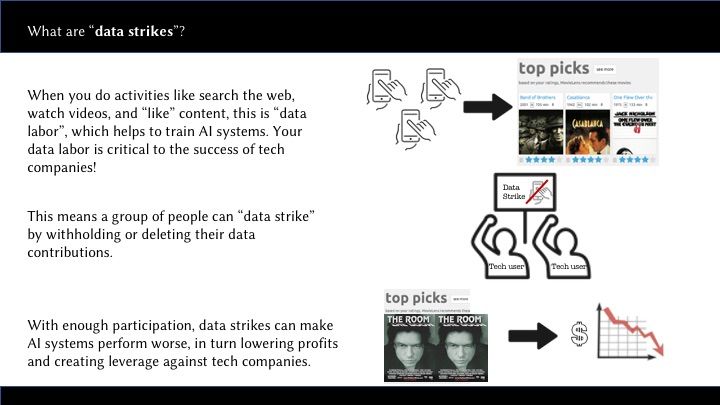

Most of the common actions you perform when using modern tech, such as “liking” posts, viewing content, sharing photos, writing reviews, and even just clicking links, can be understood as “data labor”. Your “data labor” fuels the economic success of data-dependent artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. If you’ve ever watched a YouTube video, you’ve helped YouTube’s AI technology recommend videos to others. If you’ve ever edited English Wikipedia or upvoted a Reddit post, you’ve played a role in preparing training data for GPT-3, OpenAI’s “astonishingly powerful” language generation system.

You are effectively an employee of tech companies through your “data labor”. This means that you have a new form of protest against tech companies, which we are calling “data strikes”. Data strikes require many people to join together in collective action, which an organization like the Data Dividend Project is well-positioned to organize.

What is a data strike?

At its core, a data strike is simple: a group of people decides to withhold its “data labor” from an AI technology that relies upon it.

In a data strike, participants might, for instance, stop rating products, stop writing reviews, use browser extensions to limit the collection of behavioral data, or engage in mass data deletion campaigns. Typically, all of these activities provide a free “data labor subsidy” that fuels highly-profitable AI technologies such as search engines and recommender systems. By reducing or eliminating this subsidy, data strikes have the potential to make AI systems far less intelligent, and thus far less valuable.

One thing that is particularly exciting about data strikes is that they are less painful for participants than traditional boycotts. Quitting Amazon or Facebook may be unfeasible for many people, but data strikes present a new low-barrier-to-entry means to protest tech company behavior while still using a company’s services.

The potential leverage from data strikes could help address concerns about the negative impacts of tech companies, for instance by pushing companies to support some form of “data dividend” (for instance, in the form laid out by Data Dividend Project, or in other forms).

Just a few years ago, actually organizing a data strike may have seemed impossible. Without any formal way to request “data deletion”, you would be stuck withholding future data contributions. However, with various regulatory developments like the European Union’s “GDPR”, and most relevant to the Data Dividend Project, California’s “CCPA”, using the threat of data deletion for large-scale collective bargaining is much more realistic.

Simulating Data Strikes

In our paper, we simulated the effects of versions of data strikes against recommender systems, the type of AI that powers product recommendations (e.g. “Top 10 Movies For You”). Although we are very early in this research area and our results should be taken with the correspondingly large grain of salt, what we found was optimistic for those seeking to gain leverage in their relationship with tech platforms.

We observed that data strikes can be quite powerful. A moderately-sized data strike that includes 30% of all users took away as much as half of the “intelligence” of the recommender system. If this type of strike were organized, companies would likely be motivated to listen to strikers’ concerns. Even small data strikes by users with a shared interest, like a group of comedy movie fans could be effective, as they could particularly hurt a recommender system’s ability to recommend comedy movies.

To be effective, data strikes require collective action: a single person on their own cannot meaningfully impact AI performance. However, working together, people collectively can meaningfully reduce AI effectiveness.

Conclusion

Data strikes provide a new form of protest against tech giants that may be much easier to participate in than boycotts. Given that an effective data strike requires collective action, an organization like DDP is well-positioned to orchestrate an efficacious data strike campaign.